Episode #93: Cherchez La Femme, or The Woman Behind the Art--Berthe Weill (Season 11, Episode 2)

There’s a phrase in the French language that goes, “Cherchez la femme.” In translation, it means “find the woman,” or “look for the woman,” and typically it’s derogatory, a phrase used as an explanation for the reasons why a man may be behaving badly. Cherchez la femme, some say, meaning that “woman troubles” are assumed to be at the core of any man’s real problems. But I like the idea of appropriating the phrase “cherchez la femme” to mean that we’re going to look for the women who made things right in art history, who bolstered and brought attention to some big-name artists.

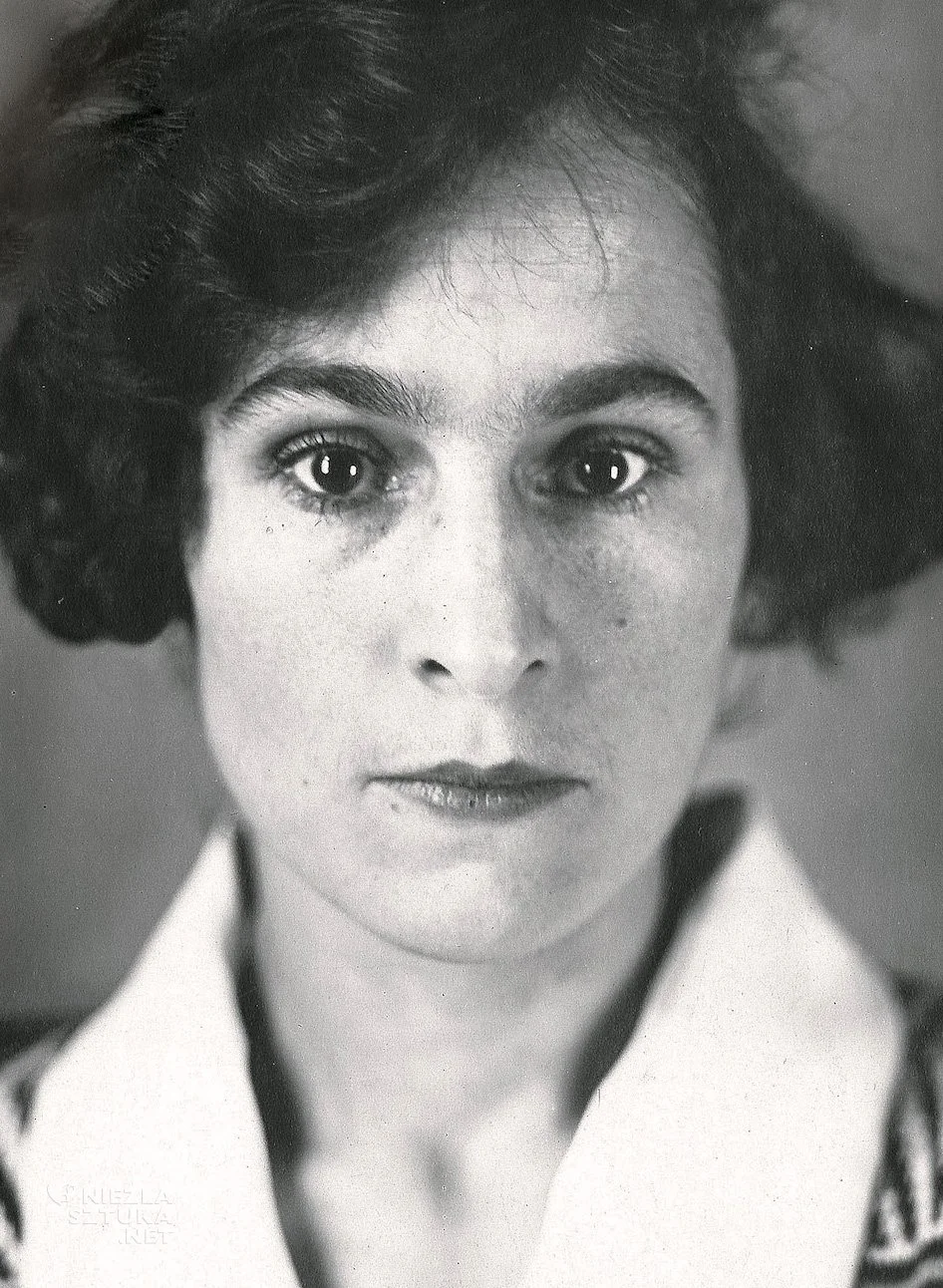

Welcome to season 11 of ArtCurious, where we’re highlighting the lives and work of the women who supported some of the world’s favorite artists. Today, meet Berthe Weill, an art dealer who made many artists famous, including some of the biggest names of the 20th century.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts and FOLLOW on Spotify

Don’t forget to show your support for our show by purchasing ArtCurious swag from TeePublic!

SPONSORS:

Kiwi Co: Get 30% off your first month plus FREE shipping on ANY crate line with promo code ARTCURIOUS

Indeed: Listeners get a free $75 credit to upgrade your job post

Betterhelp: Get 10% off your first month of counseling

GEM Multivitamins: Get 30% off your first order

Want to advertise/sponsor our show?

We have partnered with AdvertiseCast to handle our advertising/sponsorship requests. They’re great to work with and will help you advertise on our show. Please email sales@advertisecast.com or click the link below to get started.

https://www.advertisecast.com/ArtCuriousPodcast

Episode Credits:

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Additional music by Storyblocks. Research help by Mary Beth Soya.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Amazon Affiliate Program and the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, affiliate advertising programs designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org and amazon.com. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Episode Transcript

I don’t talk about it much simply because it happened about a million years ago, but an interesting segment of my art education was the time I spent working at an art gallery in Los Angeles between my stints in graduate school. It wasn’t for me, for several reasons, but I’m still so glad I had the experience, because it taught me to use several parameters to identify and consider a work of art’s value. I considered the edition number of a print or a photograph. I scoured a painting’s surface for damage or repairs. I used size, media, the artist’s background, and more to help come up with a sense of how much a gallery could charge for its sale. In short, it made me a connoisseur, in the best sense of the word. It’s a skill that I was able to hone slowly, with time, exposure, and guidance.

Being a connoisseur takes practice, but the best ones can not only quickly identify something of quality, of major interest—they might also be able to see things about the artwork that the rest of us can’t see yet. Potential. A new direction. The next big thing.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, more outrageous, or more fun than you can imagine. In ArtCurious Season 11, we’re highlighting the lives and work of the women who supported some of the world’s favorite artists. Today, meet Berthe Weill, an art dealer with incredible foresight who made many artists famous, including some of the biggest names of the 20th century. This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

If the name “Berthe Weill” sounds a tad bit familiar to you, it may be because we mentioned her gallery all the way back at the beginning of season 8, when we opened our discussion on some of the most expensive works of art sold at auction by referencing a painting by Amadeo Modigliani, which was shown in the only solo exhibition of his artwork to occur during the artist’s lifetime. Modigliani’s career-making show was a shocking one, attention-grabbing because of one of Berthe Weill’s ballsy moves: placing Modigliani’s paintings in the front window of her gallery, a window that oh-so-conveniently faced out toward a police station across the street. That may not seem like a big deal at the outset, but Modigliani’s paintings, like Nu Couché, featured naked women sporting—shock of shocks!—body hair. The police, scandalized, demanded that Weill removed the paintings, and she eventually did, but only after enough time had passed to make Modigliani’s nudes—and her gallery—a major place to see art and engage with the avant-garde in Paris.

So who was this revolutionary and forward-looking art dealer who gave Modigliani his big shot? As we’re about to find out, she was one of the most fascinating women in the world of art dealers in Europe, someone with an incredibly long-lasting legacy, but whose name hasn’t quite reached the highest echelon of praise because, perhaps, she was a woman, and a Jewish woman at that. It’s time to give much-needed recognition to the great Berthe Weill.

Esther Berthe Weill was born on November 20th, 1865, to a large but modest Jewish family, with Berthe, as she was known, as all of her siblings were equally known by their middle names—as the fifth of seven children. Most of the familial support seems to have come from the family’s patriarch, Salomon Weill, because their mother, Jenny Lévy—who was obsessed with theater and would spend most afternoons at the Comédie Française—was a bit checked out in terms of childcare. So, it was the Weill children who had to pick up the slack for the financial health of the family as a whole—remember, the Weill family wasn’t a wealthy one, so each child needed to be able to make their way in the world. Salomon Weill’s aim was to gain apprenticeships for his kids, but Berthe’s health during childhood was a bit precarious, so she needed to be able to choose a position that allowed her to work without taxing herself terribly—which is how she ended up working with a distant cousin named Salvator Mayer, a prints and curiosity dealer working at the center of Paris’s thriving art market. Berthe began working with Mayer in the 1880s while still a teenager, and she stayed there for quite a while, working with him for at least a decade. And it was there, under Mayer’s supervision and guidance, that she began training the most important part of art dealing: her eye. After years of looking, really paying attention, Weill began to understand the differences between a quality print and a shoddy one; to identify a sellable antique and separate it out from an unsellable piece of junk. She could look at something and quickly understand its value.

In 1897, Salvator Mayer died, which was a sad event, naturally, but also a fortuitous one: it granted Berthe Weill a release so that she could move toward establishing her own gallery and her own future. Alongside her brother Marcellin, she opened a gallery that focused predominantly on antiques and printmaking, just as Salvator Mayer had done and in what she had trained as an expert in her own right. And Berthe and Marcellin did okay, for a while, but their differences in management of the gallery, would eventually cause them to part ways. And I’m of the mind that it is a very good thing that Berthe stopped working with her brother, because her interests were already beginning to change—and it was her new directions and excitements that would put her in the history books.

Around 1900, the Weill family gallery caught the attention of an important Parisian art critic named Claude Roger-Marx, who likely visited the gallery because of his own interest and knowledge in printmaking. While there, he struck up a conversation with Berthe, and the two became friends, with Roger-Marx sharing his opinions on the art market with his new protégée. And his opinion was that modernism was where it was at—the avant-garde, Berthe, he cried! The avant-garde is where you should focus your energies! And Weill was intrigued, to say the least. The world of avant-garde art in Paris had been truly HUGE for the better part of the previous decades, with some art historians believing that the realist and Impressionist artists who founded the landmark Salon des Refusés had birthed the wide-ranging term of “avant-garde” to refer to those artists who experimented and played by their own artistic rules rather than rotely emulating the works of those who came before. We’ve discussed the Salon des Refusés, that first major anti-exhibition, in previous episodes, but it set a new standard in many ways, allowing the temperaments and interests of the artists themselves to be more prominent. And that’s something that appealed to Berthe Weill. She loved being able to understand an artist’s personality in their works, to feel their energy—and if she wasn’t able to sense those characteristics, then a work of art wasn’t considered good enough to be sold at her gallery.

There was someone whom Weill considered to be “good enough” pretty early on. While still working with her brother, she met a Catalan living in Montmartre who was tasked with getting more promotion and play for Spanish visual artists, and it was through this man that she met another Catalan—a young man named Pablo Picasso. According to Weill, the first work that grabbed her attention was Picasso’s 1900 Le Moulin de la Galette, a bright and garish Parisian nightlife scene now in the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. It’s not the typical Picasso painting that you’re imagining—no Blue or Rose period here, and certainly not Cubism quite yet, and it owes much to the works of Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec as much as anything else, but Berthe Weill noticed its power anyway—and she became the first art dealer to sign Picasso, who was then just 19 years old and who, by the way, was still living in Spain at the time. Weill got her first big client, and Picasso his first big ally.

Berthe Weill makes a big move in 1901—and we’re going to share all about it next—right after these quick messages. Remember that by supporting our advertisers, you keep us going! Thanks for listening.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

In 1901, Berthe Weill and her brother, Marcellin, faced a crisis, spurred on by their differing ideas for the direction of the gallery and their varied managerial styles. When the situation came to a head, the siblings broke off their partnership, but Berthe was undeterred. She wanted to be an art dealer, wanted to sell avant-garde works by fresh, young artists. That was never in question for her. And so she did something that was rather revolutionary for the time: she started her very own gallery, completely independently, using her dowry of 4,000 francs to pay for the space and its renovation. Now, this was considered a rather risky endeavor for two reasons: the first is that she worked only in the avant-garde arena, so she was choosing to showcase the works of artists who, at the time, were unknown to most of Weill’s clientele. Neither she nor her artists had name recognition to support them, so it was a perilous choice for someone just starting out on her own. But the even bigger problem was that Berthe Weill went into business by herself as an independent, single woman. During this juncture in French history—and certainly in other parts of the world as well—the idea of a woman running her own business, especially in a male-dominated field like art—was almost unfathomable, and it also wasn’t rare that women’s property was automatically transferred to their husbands when they married. But Berthe Weill did not want that—she wanted to do things herself, and on her own, so she made two big moves right off the bat. The first is that she hid her gender by naming her gallery “B. Weill Gallery,” rather than identifying herself with her first name. And secondly, she refused any marriage proposals that came her way during her lifetime. She never married—and more than anything, that was a safeguard she enabled for herself so that she could live the life she wanted to lead. If there’s one thing that we can say about Berthe Weill, it’s that she was filled with an immense courage and an immense understanding of herself and what she wanted—no easy feat.

With the opening of the B. Weill Gallery in 1901, Berthe Weill officially became the first female gallery owner in Paris, and one that was dedicated, as her business cards noted, as a, quote, “place for youth.” Weill’s commitment to the avant-garde is amazing, and the list of amazing artists whom she represented and exhibited is almost laughable in how incredible it is: she continued to fervently promote Picasso’s works, showcasing his landmark Blue Period as early as 1902. In her earliest years, she was drawn to Fauvism, the exuberantly colored style adopted by Henri Matisse and his cohort, and legend has it that Weill was the first to give that group a gallery exhibition. She represented Georges Rouault, Francis Picabia, Kees van Dongen, Georges Braque, Raoul Dufy, Maurice Utrillo, and Suzanne Valadon, big names all. When Diego Rivera lived in Paris, from 1911 through 1920, she was the only art dealer to present him in a solo art exhibition, and she adopted cubism and its daring explorations of form long before any other dealers did. That eye of hers: it was extraordinary. And her vision of what would make a good work of art? Iconic. So much of the greatest hits of modern art, as funneled through Paris in the early decades of the 20th century, have so much owed to her.

Not that it was easy—neither for her, nor the artists. At first, her gallery was so small that she would crisscross lines of rope across her space so that she could hang canvases by clothespins to make up for a lack of wall space. She even used the gallery as her makeshift home for a while, eating and sleeping there when the workday was done. And as I mentioned previously, she took a risk in choosing to showcase artists who were young, up-and-coming, experimental, and diverse. A fair share of art buyers at the time thus overlooked her and her stable of painters, considering them a dicey investment. Sometimes she got lucky, and it paid off, but sometimes it didn’t work. And that made it difficult for her to retain artists as her clients, too. Because her sales weren’t always reliable, artists would often move on, and move up, to well-established, blue-chip art dealers, like Paul Rosenberg, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, or Ambroise Vollard, major players who not only had confirmed reputations and name recognition, but who also had the capital to offer substantial stipends and exclusive contracts. So, off went Picasso, off went Matisse, off went Braque. Could Berthe Weill have worked to build up funds to offer similar perks? Sure. But she knew that to do so, she would have to exhibit a slew of artists who were more profitable and sought-after, and that was a no-go. She would sacrifice her comfort, her financial stability, and the reputation of her gallery to support the artists she loved and believed in—but she never sacrificed her vision.

Sometimes, though, that vision caused some issues. That’s coming up next—right after this break. Come right back.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

Berthe Weill had the gift of identifying great work by soon-to-be-great artists, and she supported them—and her visions for them—without wavering. If she believed in something, in someone, she didn’t hesitate to back them up. But sometimes her fervent dedication to them—and to airing her opinions loudly—led to some skirmishes. This is where the famous exhibition of Amadeo Modigliani’s nudes comes into play. As she was wont to do, Berthe Weill gave the young Italian upstart a shot at capturing the attention of the stodgy Parisian art world, and when Modigliani arrived with the paintings for his upcoming solo exhibition, Weill had a choice. Recognizing the sensitive nature of the hirsute female nude—bearing not only wisps under her arms, but also a small triangle of pubic hair, which was not the norm in art history at the time—Weill could have hung the paintings in the back of her gallery, away from the public. But she went bold, and in the entirely opposite direction. She had a history of using her storefront windows to express her political opinions, for example, and what better way to showcase her rebellion against the prudish Parisian bourgeoisie than putting those furry nudes front and center? It sure caught the attention of Paris, but not without her reputation being dragged down a bit—and not before Weill herself was dragged down to a nearby police station after refusing to kowtow to a constable’s orders to remove the offending works from her own window.

One of the things I love most about Berthe Weill, unsurprisingly, is her commitment to other women. About halfway through her 40-year-career as a gallerist, she made a conscious decision to devote nearly half of her exhibitions to the works of women artists—many of whom, like Picasso and Modigliani before them—were enjoying their first exhibitions because of Weill’s work and attentions. This is truly awesome, especially keeping in mind the lack of disparity that we still see today regarding gender in museum and gallery exhibitions, not to mention disparity in race, class, religion, and more. Berthe Weill was ahead of her time, a true visionary.

Berthe Weill ran her art gallery in a few different locations in Paris from 1901 until 1941, when the Second World War caused her to shutter it. At the risk of stating the obvious, the war was rough on Weill—mostly because she was Jewish, and she spent most of the war years avoiding anti-Semitic activity and persecution. Even before the onset of the war, the rising tide of anti-Semitism in Europe had taken a toll on Weill and her gallery, and that, combined with equally rampant misogyny, meant that Weill never really found success during her lifetime. After the end of World War II, her savings were depleted, leaving her destitute—but a small lifeline appeared. A congregation of artists and fellow art dealers came together in 1946 to hold a special fundraiser, donating over 80 works of art for sale, with all proceeds going to support Berthe Weill, the smart, dedicated art dealer who had given a start to so many and who had stayed loyal to them all. Let that sit with you for a moment, because it’s a sweet testament to the level of respect that Weill garnered. The fundraiser helped—Weill, who was eventually recognized as a chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French Republic--was able to manage a meager retirement in her little apartment, passing away at age 85 in 1951.

In the biographies of artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Modigliani, Berthe Weill is mentioned, yes—but not as much more than an aside or a footnote, perhaps with the brief exception of Modigliani. But she deserves to be a much bigger part of their histories, and the history of 20th century art. Part of the reason that Weill has received so little attention in the past is due to so many of the things we’ve already discussed today, some good, and some bad, but all brought together like the many heads of a Hydra from Greek mythology: antisemitism, misogyny, Weill’s devotion to the avant-garde, her risk-taking, her lack of major funds. Writers like Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, ungenerously described her as, quote, “a homely Jewish spinster with spectacles thick as goldfish bowls.” Unquote. Such characterizations are totally gross, and they also lead readers to dismiss her as unimportant to the narratives of these artists’ lives. Luckily, we have the work of a new generation of researchers, like the French art historian Marianne Le Morvan, who has worked for more than a decade to establish an archive and biography of Berthe Weill—it was she, by the way, who discovered an auction catalogue that confirmed that 1946 fundraiser in support of Weill. Le Morvan is truly undertaking a massive challenge, since Weill left behind so little—no surviving correspondence, inventory records, and the like. But what we do have is her 1933 autobiography, which Le Morvan has been translating. In Pan! Dans l’œil (which roughly translates to Boom! Right In the eye!), Weill acknowledged that she, quote, “took a risk of going modern,” unquote, a risk that makes her stand out as the great discoverer of so many of the greatest artists of the century, a tastemaker and changemaker. She was a great supporter of women artists and stands out as someone who paved the way for other female art dealers and gallerists. It didn’t come easy—it still isn’t coming easy. But perhaps Weill never expected it to be. As she declared in her autobiography, “ To struggle! To defend oneself! That is the story of my life.”

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal. HUGE thanks to Mary Beth Soya for her awesome research for this episode and for nearly all of our episodes this season. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, and our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com. Our podcast services are provided by our friends at Kaboonki. Subscribe now to their show, Subgenre, a podcast about the movies. Season 1 is available in its entirety now—please visit subgenrepodcast.com for more details. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator, which means you can donate tax-free to “ArtCurious” to show your support. To find the donation links and for more details about our show, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod. And we have podcast merchandise! Check out the link to our TeePublic store in the show notes on this episode, or on our website.

Check back with us soon as we explore the facts, and the fictions, of the unexpected, slightly odd, and strangely wonderful in art history.