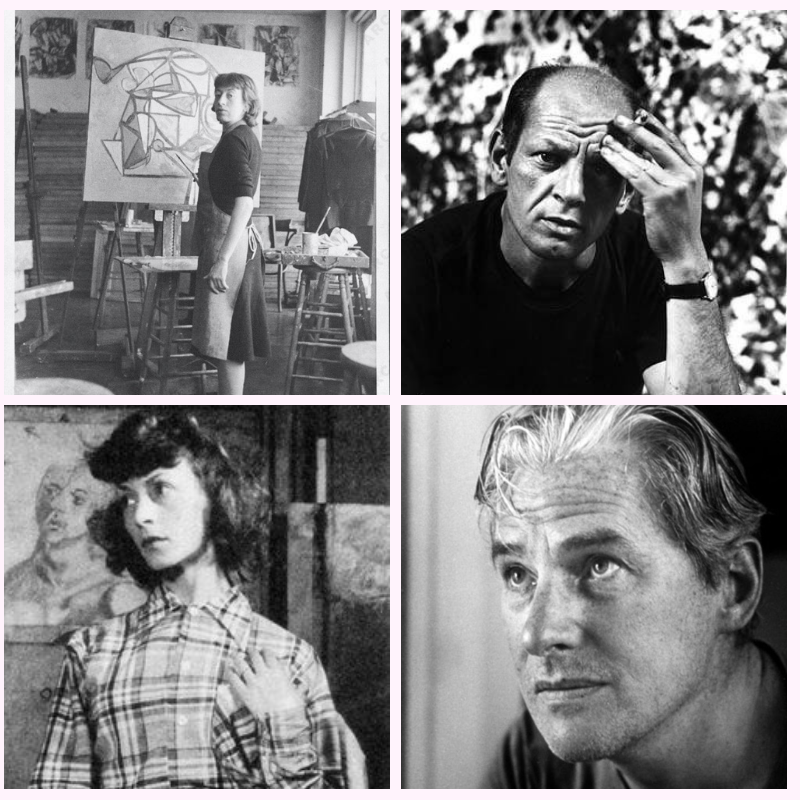

CURIOUS CALLBACK: Episode #35, Rivals-- Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning vs. Their Husbands

Anyone familiar with Abstract Expressionism will tell you that this art movement was one where all the insiders or practitioners were more closely involved than many other art movements. Such close confines also made for some serious rivalries, too. But there were other artists who were more intimately involved with one another and their artistic process-- they were married, or were lovers. Such is the case with both Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning --both of whom married women who were incredible artists in their own right. Interestingly, and sadly, when these two spouses are mentioned, it’s very rare that we are treated to sincere commentary just about their works of art. More often than not, we are, instead, given explanations of how these women measure up to their (admittedly more famous) husbands, and are relegated either to a supporting role, or just plain seen as not good enough in comparison. Why is it that such talented women continue to have their posthumous careers and stories marked and shaped by their husbands?

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts and FOLLOW on Spotify

SPONSORS:

Lomi: Enjoy $50 off a Lomi Composter by visiting our link and using promo code ARTCURIOUS

Mau: Upgrade your cat furniture stylishly and sustainably at maupets.com.

To advertise on our podcast, please reach out to sales@advertisecast.com or visit https://www.advertisecast.com/ArtCuriousPodcast

Episode Credits

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Additional research and writing for this episode by Patricia Gomes.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits

"Song Sparrow" by Chad Crouch is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; "Converging Lines" by David Hilowitz is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "Today, Tomorrow, & The Sun Rising" by Julie Maxwell is licensed under BY-ND 4.0; "Is everything of this is true?" by Komiku is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal License; "Fantasy in my mind" by Alan Špiljak is licensed under BY-NC-ND 4.0. Ad Music: "Hello September" by Proviant Audio is licensed under BY-NC-ND 3.0 US; "The Valley" by Dee Yan-Key is licensed under BY-NC-SA 4.0; "Galaxies" by Split Phase is licensed under BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and further resources

The Art Story: Lee Krasner

Artsy: "The Emotionally Charged Paintings Lee Krasner Created After Pollock's Death"

Smithsonian Magazine: "Why Elaine de Kooning Sacrificed Her Own Amazing Career for Her More Famous Husband's"

National Portrait Gallery Blog: "Elaine de Kooning's JFK"

NPR: "For Artist Elaine de Kooning, Painting was a Verb, not a Noun"

Episode Transcript

Anyone familiar with Abstract Expressionism would basically tell you what I’m about to tell you: that this art movement was one where all the insiders or practitioners were more closely involved than many other art movements, though of course there are exceptions. Most AbEx artists were friends, working together, collaborating, bouncing ideas off of one another. Such close confines also made for some serious rivalries, too. But there were other artists who were more intimately involved with one another and their artistic process-- they were married, or were lovers. Such is the case with both Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, who were the subjects of our last episode. Both of these men married women who were incredible artists in their own right. Interestingly, and sadly, when these two spouses are mentioned, it’s very rare that we are treated to sincere commentary just about their works of art. More often than not, we are, instead, given explanations of how these women measure up to their (admittedly more famous) husbands, and are relegated either to a supporting role, or just plain seen as not good enough in comparison. Why is it that such talented women continue to have their posthumous careers and stories marked and shaped by their husbands?

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. And today, we are continuing our series on great rivalries in art history with the unfortunate unofficial rivalry that history often likes to perpetuate: the comparison between Elaine de Kooning and Lee Krasner and their artist-husbands. Welcome to the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

We should begin our episode today with a brief disclaimer of sorts. By no means are either of these women-- Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning-- unknowns who made little to no mark on the art world. Both of them had serious careers before, during, and, in the case of Lee Krasner, after their marriages to those two biggies. After Elaine de Kooning died in 1989, her reputation as a feminist, free-thinker, and art critic has only risen in esteem and popularity, and her work has been featured in several solo exhibitions across the globe, including a well-received exhibition of her portraits in 2015 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Lee Krasner is probably the more well-known of the two women, and the first major retrospective of her work occurred at the Museum of Modern Art in New York back in 1984, long in the works at the Museum and taking place, coincidentally, only months after Krasner’s death in June of that year. Regardless, by no stretch of the imagination would you be able to call either of these artists a household name-- and even some art history students who have little training in the ways of modern art might not even be aware of either of them (or they mistakenly assume that Lee Krasner was a man, simply based on her name alone). But surely in this newly rising tide of feminism and interest in women in the arts, we can see this as an opportunity to recoup these stories that center women and put them in the spotlight-- and to question why they aren’t already there in the first place.

Lenore Krasner-- who also went by the name Lena--was born on October 27, 1908, in Brooklyn, New York, to a family of Russian-Jewish immigrants. At the age of 13 she was already bound and determined to become a professional artist and made the decision to apply to Washington Irving High School, the only New York City public high school that allowed girls to study art at that particular period. Lenore knew that she had a bit of a challenge ahead of her. In the early 1920s, it was unusual for women to become professional, successful artists, let alone a child from an immigrant family. But it was her gender that, time and again, would cause a problem for her. Early on, the works that she created in school was criticized by her art instructors because her experimental, innovative style was deemed, quote, “unfit for a woman.” It has been long been assumed that Lenore chose to go by the moniker “Lee” in her professional life in order to disguise her gender and to ease her way into the boys’ club that art was, and always has been.

Thankfully, Lee Krasner’s art education was extensive. After high school, she studied first at Cooper Union, where she received a scholarship to attend the Women’s Art School. After that,she moved on to the prestigious National Academy of Design, where she stayed for four years, between 1928 and 1932. She also took some courses at the Art Students League, the same place where both Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning would work to hone their own talents. Lee Krasner was dedicated and she was all-in with her studies, so it isn’t surprising to hear that she was rewarded for it. In 1933, she obtained full-time work as an artist through the Works Progress Administration of the Federal Art Project, a visual arts program within Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. The WPA hired hundreds of artists under this project, who collectively created more than 100,000 paintings and murals and over 18,000 sculptures in various public institutions around the country, including public schools, municipal buildings, hospitals, and so forth- and you might recall from our last episode that both Pollock and de Kooning scored positions with the WPA, too. But Krasner was different-- she advanced quickly to a supervisory position when other artists dropped out. One of the artists she would end up supervising, by the way, was her own husband, Jackson Pollock. Her work at the WPA, though, was not as interesting to her as the experiments with abstraction that was swirling around New York at the time, so though she was thrilled to be able to pay her bills by creating art, it appears that it was less than fulfilling. Still, she kept herself in the know in the art world and among those whose works did interest and excite her. She joined organizations like the Artists Union and American Abstract Artists, becoming friendly with with Arshile Gorky, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, and more of the most influential movers-and-shakers of the day.

Regardless of Lee’s affiliation with all of these artists and organizations, there is still really only one name with whom she is constantly associated. And that, of course, is Jackson Pollock. As discussed in our last episode, Pollock and Krasner met in 1936 while both worked at the WPA, but their connection wasn’t tangible then, and they didn’t spark to one another until after they were reintroduced in 1942. They married three years later. But the fact that Krasner rose in prominence and esteem before Pollock did isn’t actually discussed very often. Remember that it was she who introduced him to Willem de Kooning, his own artistic rival. But the frustrating thing was, and still is, that Krasner’s work is, too frequently, not separated from that of her husband. And as such, it’s almost like Lee Krasner’s works get pitted, by comparison, with Pollock’s, something that Krasner had to tackle head-on while she was still alive. About their work, she said, quote, “Painting is revelation, an act of love. There is no competitiveness in it.” To her, they weren’t in competition as fellow Abstract Expressionists— instead, they were in conversation. But for the rest of the world, there was a hierarchy at play, and in traditional art history, it reads like this: Jackson Pollock, art god. Lee Krasner: supporting figure.

To be fair, it is a fact that Krasner’s artistic life changed considerably after her marriage to Pollock. While she never stopped painting, she wasn’t quite as prolific as she once had been, and her determination to get her works shown and seen just wasn’t her top priority. Her husband’s career was. She stepped back from her own plans to effectively manage his career. She was his biggest fan, doing her very best to not only champion his art, but also to promote it— trying to secure him exhibitions and purchases, on top of just keeping their household together, not a small feat when you are dealing with someone who is an alcoholic. Later in life, Krasner claimed that the main reason that she and Pollock never had children was because Pollock, in many ways, was too childlike himself, often relying on her in such a needy fashion that Krasner’s maternal instincts were directed fully towards him. And of course there was the drinking to contend with. Given all of these factors, it isn’t too much of a surprise that Lee’s art took a backseat almost totally. As she said, quote, “It wasn’t Jackson who was stopping me, but the whole milieu in which we lived.”

When their 11 year marriage ended with Pollock’s death in his 1956 automobile crash, Krasner didn’t rescind her promise to act as his promoter and caretaker. In fact, she spent much of the remainder of her life working to ensure his legacy— but she also finally allowed herself to have the time and space to continue her own artistic journey. In the decade immediately following Pollock’s death, Krasner created some knockout pieces called the “Umber” series, so named for their earthy tones of brown and cream. Krasner was an insomniac, so a large chunk of her works were done at night, and in choosing to work at that time, she also opted to minimize her use of color due to the lack of bright lights available to her at that particular time of day. These paintings are expressive, curvy, and more gestural than many of the works that came before. Though limited in color and tone, they seem more open and free at the same time. But when they were finally exhibited in 1959, they were slammed by critics like the influential Clement Greenberg, who chided Krasner for looking back towards the past— and back towards Pollock. Some said that she was being influenced by Pollock from beyond the grave; others said that she was trying to exorcise his ghost. But either way, her work couldn’t be seen on its own accord. From the very beginning, that knee-jerk comparison with Pollock was right there.

This automatic response is one which Elaine de Kooning implicitly understood. She was born Elaine Fried ten years after Lee Krasner, on March 12th, 1918; and like Krasner, she was also a Brooklynite. As the oldest of four children, Elaine frequently stepped in as a caregiver for her siblings due to her mother Mary Ellen’s inattention; it reached a terrible pinnacle when, at one point, Mary Ellen was sent to a psychiatric facility for basically being an absentee parent. But Elaine Fried defended her mother throughout her life and said that much of what she provided was actually really good for their family. And one of the things that she did well was was early, loving exposure to art. Mary Ellen took her kids to museums like the Metropolitan frequently, and it made a huge impression on Elaine. She began drawing images of her classmates at school, and selling them, too, just like young JMW Turner had done a century before her. After high school, she did a quick stint at Hunter College in Manhattan before dropping out to attend the Leonardo da Vinci Art School located on 3rd Ave and 34th Street. There, she was taught by artists under the umbrella of the Works Progress Administration, who noticed her for her daring, ambition, and her feminine wiles. We’ll get back to that one in a moment.

Let’s fast-forward the tape a little bit to get a real sense of the importance of Elaine de Kooning’s work. At the peak of her career, she participated in the 1961 edition of the famous Whitney Biennial, an influential show still going on to this day and typically presenting some of the best and brightest in American contemporary art. And her work garnered some attention, including some serious high-level interest. In 1962, she received a prestigious commission to paint an official portrait of John F. Kennedy for the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. The work is now a popular one in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the Gallery’s website notes that the artist was a, quote, “unorthodox choice for the task, not only because she was female, painting in the abstract expressionist style, and highly individualistic, but also because she had executed few commissioned works in her career… But Elaine’s skill at recording the essence of a subject in a few sittings won her the job.”

The painting of JFK might be her most thoughtful portrait, and is probably her most well- known work. It’s remarkably different than many of the presidential portraits that came before-- there’s no formality or pomp or any symbols or trappings of power and politics. Instead, we see JFK seated in a green chair, legs crossed, one arm gripping the chair and the other one draped, relaxed, across his knee. He looks like he’s about to rise up and walk straight out at us. And there’s such an energy and vibrancy to the painting-- due to the bright, splashy colors and the frantic brushwork-- that we almost believe that he will walk straight out at us. Everything about this work screams youth, motion, the future, the now, and we are helpless to do anything but stare into JFK’s eyes, which Elaine called “a total surprise,” and the “violet [color] of grapes.” It’s magnetic and an undeniable showstopper of a piece of art.

As she grew into her own as an artist, Elaine always defended Abstract Expressionism, though she was really only tangentially involved with the movement. Within her own work, she retained her interest in figuration throughout her life, and in numerous series— her Bullfights from the late 50s and early 60s, her ongoing obsession with basketball players in a series that spans 40 years, and in many other works-- de Kooning brought the expressive gesture of Abstract Expressionism to bear on figurative subjects. Elaine de Kooning felt that making portraits was like falling in love — "painting a portrait is a concentration on one particular person and no one else will do," she once said. She showed many of these works at several solo gallery exhibitions throughout her lifetime, as well as at museums including the Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey, and the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, New York. She also went onto teach at several acclaimed universities in the U.S., including becoming the first distinguished visiting professor in art at the University of California, Davis, my alma mater, where she was invited to work with none other than pop genius Wayne Thiebaud.

So-- if Elaine de Kooning was this successful and well-respected in the art world in her own right, why is she rarely discussed as an artist except in relation to her famous husband? This question is still one that haunts collectors, educators, and curators today. Even a 2015 article in Smithsonian Magazine made it blatantly obvious with a headline that read “Why Elaine de Kooning Sacrificed Her Own Amazing Career for Her More Famous Husband’s”? Why indeed. Probably she felt that she didn’t have much of a choice because her talent and output certainly wasn’t, or isn’t, to blame. Brandon Fortune, curator of an Elaine de Kooning exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in 2015, remarked that Elaine was probably always pretty aware of her strengths, noting, quote, "She said and she thought she was as good as any male artist.” But, like Lee Krasner, she was beholden to a society that just kept women at bay a little bit.

Elaine Fried met Willem de Kooning in 1938, after they were introduced by a mutual friend, and it was apparently love at first site. They got close when Willem gave drawing lessons to Elaine, and even though he was a strict teacher, she was won over by him and his work. In 1939, the year after the two artists met, she moved into Willem's studio and they got married four years later, in 1943. They had a long marriage--one that spanned 46 years, even though they lived apart for almost half of that time. It seems that opposites really attracted in this case: Where she was social, he was antisocial, where he was gloomy, she was lively, and so on. It was, at times, a tumultuous relationship. But it’s possible that the taciturn Willem needed gregarious Elaine by his side to really succeed in the art world-- and she knew it. As Brandon Fortune notes, quote, “She knew so many people. She was at the red hot center of everything that was happening in New York.” She used this to her advantage-- and to her husband’s advantage-- by often having affairs with people who could positively drive her husband’s career. Remember those feminine wiles that frequently attracted men to her? According to Smithsonian Magazine, she had flings with “the critic Harold Rosenberg, ArtNews editor Thomas B. Hess and gallery owner Charles Egan,” all of whom held up their end of the deal, with Rosenberg and Hess championing AbEx in general (and Willem de Kooning in particular) in their publications, and Charles Egan giving him his first solo exhibition ever. All the while, as we know, Elaine de Kooning created her own works of art. It seems that she rarely felt herself to be in direct comparison or competition with her husband. Later in her life, a friend asked her, point-blank, what it was like to work in the shadow of the great Willem de Kooning, to which Elaine gave a beautiful and loving reply: quote, “'I don't paint in his shadow, I paint in his light.”

Not that it wasn’t hard sometimes. In 1949, the Sidney Janis Gallery held an exhibition titled Artists: Man and Wife, which included Elaine and Willem alongside other art power couples: Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and, of course, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. Elaine eventually looked back on this show with regret, saying, quote, "It seemed like a good idea at the time, but later I came to think that it was a bit of a put-down of the women. There was something about the show that sort of attached women-wives to the real artists.” And there’s the rub. That separation would keep the wives in that position as “the other,” always justified with modifiers like women artist instead of just artist. Elaine may have painted in Willem’s light, but to the outside world, she still seemed stuck in his shadow.

Just because Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning had a similar experience managing and promoting their husband’s careers over their own doesn’t mean that they were all hunky-dory together. Though not much has been written about the women’s relationship, it does seem that there was a divide between them, if not some actual animosity. According to Sebastian Smee in The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals, and Breakthroughs in Modern Art, he writes that Elaine de Kooning quote “pitted herself” against Lee Krasner because of Krasner’s promotion of Pollock at the expense of all other AbEx artists. And most articles and books really stop at this point, leaving the details of Lee and Elaine’s interactions rather vague. In essence, these explanations or assumptions offered to us today are that these women acted primarily as support systems and defenders of their art-god husbands-- and that it was thus their husbands who drove these women to not have a friendly camaraderie. We could say that Lee and Elaine were rivals of sorts simply because their husbands were rivals.

People have frequently mused over the past couple of decades about whether or not these women would have had better or more successful careers had they not married such famous men of the art world. It’s an interesting question, but one that ultimately doesn’t really matter, for two reasons: one is that they did marry their husbands, so there’s no take- backs there, but the second reason is even better and more important: they were good and successful enough, as artists, in the first place. Their prominence in the art world, their sales and commissions, the respect showered on them by colleagues and critics-- it’s all there. The only thing that holds them back from being seen in the same light as their husbands is us-- our expectations, and our assumptions.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal. The ArtCurious theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, and our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com. Our podcast is co-produced by Kaboonki - podcasts, creative video, and more. Subscribe to their show, Subgenre, a podcast about the movies, available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and at subgenrepodcast.com. Kaboonki: Leave your mark. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space, Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator, which means you can donate tax-free to ArtCurious to show your support. To find the donation links and for more details about our show, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Facebook and Instagram at artcuriouspod.

Check back with us soon as we explore some of the most unexpected, slightly odd, and strangely wonderful in art history.