Episode #66: The Coolest Artists You Don't Know: Henry Darger (Season 7, Episode 6)

ARTCURIOUS: Stories of the Unexpected, Slightly Odd, and Strangely Wonderful in Art History is available now from Penguin Books!

For most Americans, there’s a list of arts that they might be able to rattle off if pressed to name them off the top of their heads. Picasso. Michelangelo. Leonardo da Vinci. Name recognition does go a long way, but such lists also highlight what many of us don’t know-- a huge treasure trove of talented artists from decades or centuries past that might not be household names, but still have created incredible additions to the story of art. It’s not a surprise that many of these individuals represent the more diverse side of things, too-- women, people of color, different spheres of the social or sexual spectrum.

This season on the ArtCurious podcast, we’re covering the coolest artists you don’t know. This week: Henry Darger.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts!

SPONSORS

The Great Courses Plus: Enjoy a free trial of The Great Courses Plus's entire library

MOVA Globes: use code "ARTCURIOUS" for 10% off your order

Episode Credits

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Social media assistance by Emily Crockett. Additional writing and research by Rachel Whitaker.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits

"Backspace" by Blear Moon is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "walking in depreston promo shorter" by Ai Yamamoto is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "Negentropy" by Chad Crouch is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; "Brushed Bells In The Wind" by Daniel Birch is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "Silent Park Inside Your Soul" by Alex Mason & The Minor Emotion is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "Drown in Mirrors" by Sergey Cheremisinov is licensed under BY-NC 4.0. Ads:"Free Time" by Mela is licensed under BY-SA 4.0 (Mova Globes)

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and further resources

Artsy: Henry Darger

Hyperallergic: The Sexual Ambiguity of Henry Darger’s Vivian Girls

The Guardian: Portraits of a serial killer?

Episode Transcript

DISCLAIMER

Please note that there is some mention of abuse in this episode, so please take care when listening.

“Are you an artist?” It’s a question that I get all the time when I mention that I work in an art museum, and especially when I tell people that I am a curator. The answer is no, I’m not an artist, at least not in the traditional “I paint pastel landscapes” or “I make clay pots” kind of way. But I understand this question a lot, because for many, working in an artistic field or an artistic institution makes the most sense if you, yourself, are an artist. When I balk and tell people that no, I’m not an artist, but I so appreciate and love the works of many artists, I often find that a kind-hearted person will tell me, “No, you’re an artist too. We all are, in our own way.” And there’s something really beautiful about that statement. Just like it’s really hard to define exactly what art is, so it is when it comes to defining who is an artist. Are you an artist if you go to art school? Are you an artist if you work as a designer or a house painter? Are you an artist if you draw in a sketchbook at home, for fun? What about if you made an amazing, 15,000-page graphic novel, building an imaginary visual world for no one but yourself?

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. IIn season seven, we’re uncovering the coolest artists you don’t know, and today, we’re looking at the life and work of Henry Darger, one of the most fascinating outsider artists of the early 20th century. This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

Let’s start with the basics: who was Henry Darger? It turns out that this might not be as basic a question as you’d think, and depending on who you ask, you may get a variety of answers. He was a simple person. He was a complex person. He was an artist. He wasn’t an artist. He was an oddity. He was an inspiration. So, you can see some of the difficulty, right off the bat, in understanding who Henry Darger was. But we do know at least some facts, which is great because Darger’s early life is most likely the key to understanding the man--and the maker-- that he would become.

Henry Joseph Darger was born April 12, 1892 in Chicago, Illinois, to father Henry Darger Sr. and mother Rosa Fullman. Not much is known about his earliest years except that when Henry was just four years old, his mother died of a severe fever and infection after giving birth to Henry’s little sister, a girl whose name is unknown to us, and even to Henry Darger himself, because Darger’s father, Henry Senior, felt unable to care for both of his children in the wake of his wife’s death. Shortly after Baby Girl Darger was born, she was given up for adoption, and her brother would never again see her or know her. This loss-- of his sister primarily-- would be noted as a seminal moment in little Darger’s life, a moment that would go on to inspire, perhaps, his magnum opus, all about young, innocent, lost girls. But first, there would be more losses to grieve.

Henry Senior and Henry Junior, by all accounts, got along well. Darger would note that his dad was kind and loving towards him, but in 1900, the year that Henry Darger turned eight years old, his father fell ill and was moved into a convalescent home for the aged and infirm. Unable to properly care for his son, then, Henry Senior was essentially out of the family picture, and little Henry Darger was transferred to a Catholic orphanage called the Mission of Our Lady of Mercy. And it was within this environment that the signs of trouble in Henry’s life began to manifest themselves. Most accounts of his childhood have implied that Darger was a little strange-- “Peculiar” seems to be the word that comes up most often. At the same time, though, there was no doubt that Young Darger was extremely smart, ahead of the curve in terms of intellect, and better at reading and writing than most other children his age due to his father’s support of literacy and learning. But such smarts didn’t do much to help Darger, ultimately, and instead he found himself on the wrong side of authority at the orphanage. After numerous outbursts, fights with other students, and in smart-alecky disagreements with his instructors, Darger was sent for a psychiatric evaluation, after which it was determined that he be institutionalized in Lincoln, Illinois, at the rather frightening-sounding Illinois Asylum for Children with Feeble Minds. Yeesh.

Not a whole lot is known about Darger’s time at the Illinois Asylum for Children with Feeble Minds, but you can imagine that it wasn’t super great. Some have extrapolated that the abuses detailed in his writings--both physical and sexual abuse--probably stemmed from this time period. Child labor, too, was part of the deal at the Asylum, so add that to the mix, and it’s not surprising to note that Darger tried mightily to escape its walls. Later in life, he recounted a distressing capture on his first escape, wherein he was caught by a boy--not much older than himself-- who was riding a horse. To take him back to the asylum, the boy tied Darger up by his hands and forced him to run--tied to the horse-- all the way back to the asylum. Luckily, by the time of his third attempt, he had managed to escape, walking away at the age of 16 and headed back home to Chicago. Not that there were many people waiting for him upon his return. Just prior to his successful escape from the asylum, Henry Darger received word that his father had died, leaving him essentially alone in the world. Thankfully, he had one person on which to rely-- his kindly godmother, who connected him, now 17 years old, to a nearby hospital-- a Catholic institution called St. Joseph’s- and it was there that Darger was hired as a full-time janitor. It would be the only job he’d hold throughout his life, and he held onto it until he retired in 1963 at the age of 71. That’s the gist of his biography. That’s the Henry Darger, the custodian, that most people knew of him during his lifetime. But it was what he did in his off-hours that made him of such interest to us today.

And that’s coming up next, right after this break-- stay with us.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

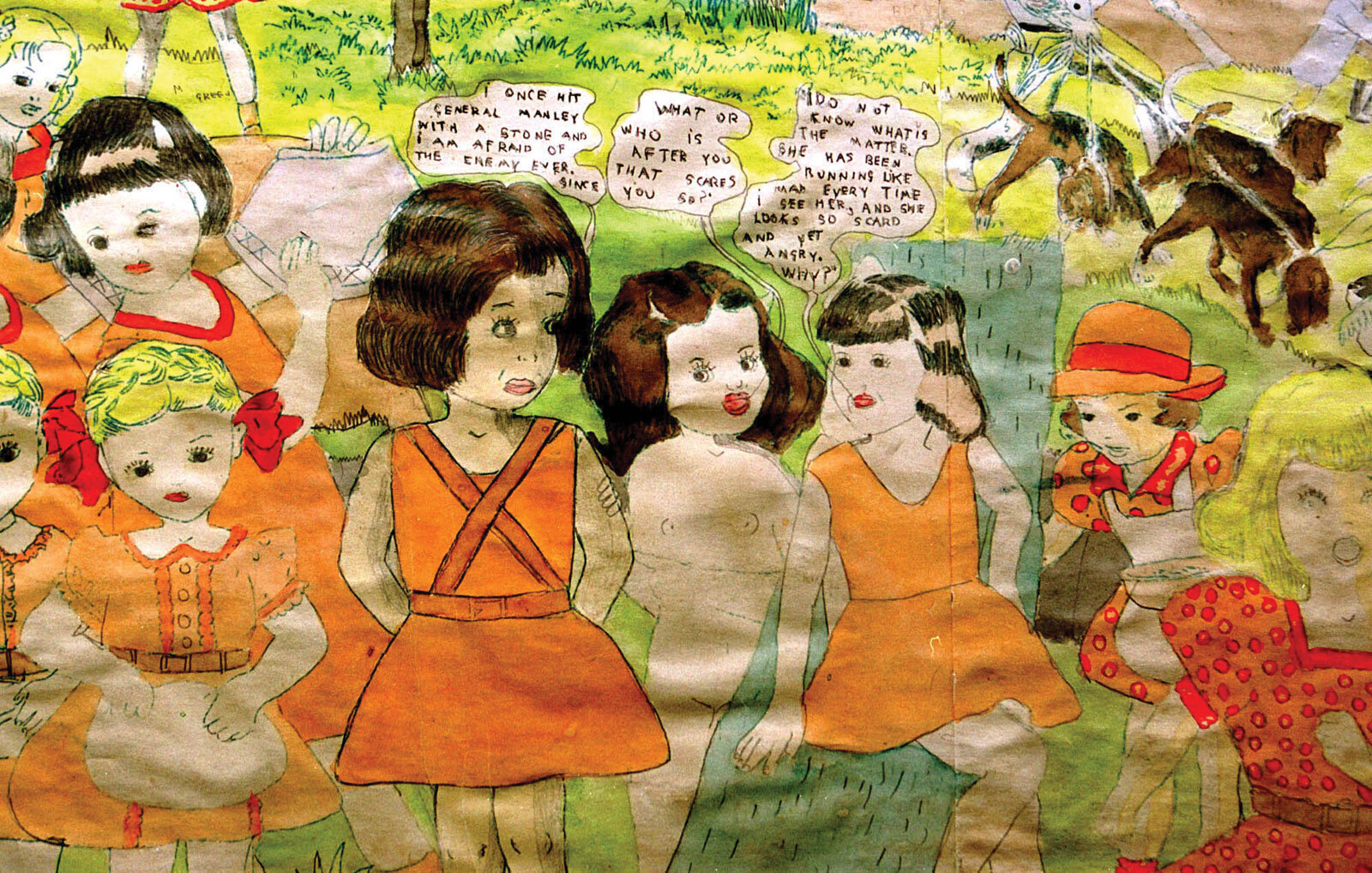

When Henry Darger wasn’t at work keeping St. Joseph’s Hospital spic-and-span, he was hard at work in his own deeply imaginative, boundless mind. Though ultra-secretive in his everyday life, at home he was expansive, concocting drawings and stories that exist in tens of thousands of pages. He produced over 30,000 pages of content over his lifetime, all about the things so often out of our control: our destinies, the battle between good and evil, and the fight for the ones we love. It all began in 1909 as a means to managing the stories and pictures that filled his head. And his process was fascinating. He experimented with drawing, collage, collage, copying, tracing, and overlay, among other methods of creation, to bring his thoughts to life. Placed on cheap butcher paper, these illustrations were then glued together to form large panels to tell a segment of his story, laid out like a storyboard and sometimes reaching up to 12 feet tall. As a completely self-taught artist, Darger knew little to nothing about art itself, or the techniques and traditions that so many other artists followed lovingly. With him, it was all personal innovation, experimentation with whatever sprang to mind--and he’d try almost anything to see if it would work. He took inspiration from little things: clippings of advertisement models or celebrities on which he’d base his characters, like the Coppertone Girl or actress Mary Pickford; plot lines from his own limited experiences, especially while growing up and in the care of the orphanage and asylum. And oh boy, did it all add up. Ultimately much of what Darger produced would become one single masterwork that makes up half of his entire artistic output: a 15,0000-page illustrated novel he called In the Realms of the Unreal, with the largest portion of the “book” sub-sectioned into The Story of the Vivian Girls, in what is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm. I know, it’s a mouthful, and you can see that Darger wasn’t into editing his titles, just as he wasn’t enthused about limiting his page count. But The Vivian Girls, which is how we’ll shortcut the title of the main section today, is an incredible and unfettered glimpse into the mind of a man who made art as a way to escape his own terrors and to understand the realities of his own little world.

But yeah, 15,000 pages. David Foster Wallace, eat your heart out.

Now, In the Realm of the Unreal isn’t exactly the easiest work to synopsize, especially given its length, but also due to its… well, its semi-inscrutability. From what I can tell, the story is about the battle between the evil Glandelinians, who were non-Christian soldiers that tortured children, and the devoted Christian nation known as Abbieannia. Heading the rebellion are The Vivian Girls, the seven princess daughters of emperor Robert Vivian tasked with ending the terrible practice of child slavery performed by the Glandelinians. Even the environment is fantastical, with the setting as a planet around which we, on Earth, orbit as a moon. As an alien planet, it’s not only mixed with the inhabitants of Abbieannia, but also with strange hybrid beasts, too. Together it is an altogether threatening and strange environment through which the Vivian Girls traverse in hopes of defeating their enemies and bringing peace to society. And it doesn’t always go well, or smoothly. Throughout In the Realm of the Unreal we see curious compositions that illustrate an array of violence, including violence towards innocent children--many of whom are depicted in various states of undress and with hints of mixed gender ideations. And as you’d expect from a story that places a Christian people against a non-Christian group, there are many subtle and not-so-subtle religious references. It’s a trip. And it isn’t easy to look at, nor easy, again, to describe in a general narrative format. Like the essential battle between good and evil, it is an ongoing conflict, lasting for thousands of pages in panoramic collages and watercolors expanding for dozens of feet. There are images of torture, of murder, of epic battles and daring misadventures, and at no point is it a foregone conclusion that the Vivian Girls, nor any other do-gooders, would win. In fact, in perhaps the most unexpected element of all, Darger conceived of two separate endings for his masterpiece: one in which the Vivian Girls are, of course, triumphant, and one where they are brutally defeated by the Glandelinians, who go on to rule the land. It’s almost like a Choose Your Own Adventure, but in a decades-long graphic novel format.

Many have questioned the origins of In the Realm of the Unreal, especially homing in on Henry Darger’s inspirations for such a strange, dark, and creative magnum opus. For someone who kept to himself so much during his lifetime, it’s certainly hard to draw many super-direct connections. But there are hints in Darger’s own autobiographical writings that point to a couple different formative moments. Naturally the loss of his unknown sister, the loss of his own parents (albeit unintentional), and the abuse he appears to have suffered at the hands of both adults and other children while institutionalized may have had a major part in the creation of this huge work. But there’s also another potential inspiration. While perusing the newspaper one morning, Darger came across a story and an accompanying illustration in the Chicago Daily News on May 9, 1911-- an awful report of the murder of a five-year-old girl named Elise Paroubek, who had disappeared around the corner from her home and whose body was discovered a month later, with the cause of death identified as suffocation. The understandable horror and uproar that accompanied this and many subsequent articles in the Chicago Daily News kept poor little Elise’s sad tale in the limelight for weeks, and Darger, furious with the injustice of child murder, kept a growing pile of newspaper clippings about the case to locate Elise’s murder. No one would ever be identified as the perpetrator. When the original May 9 newspaper clipping disappeared from Darger’s archive, possibly as part of a robbery of his belongings at work, the Paroubek story galvanized, for the artist, into a true cause, an obsession over which he would toil for decades and 15,000 pages-- as if the loss of Paroubek in both real and newspaper-clipping form could be atoned for in an epic tale of childhood bravery and vigilante justice on the part of none other than a band of seven young girls.

Darger, too, felt a part of this vigilante justice, and even identified with the quest to the extent that he wrote himself into the tale of the Vivian Girls. In particular he cast himself in the role of the General of the Christian Army of Abbieannia, a protector and savior of children like the Vivian Girls, quick to act if they were in danger and ruthless in his defense of them. Over the years there has been speculation about the real Darger’s relationship with children, especially young girls, given his focus on them in his art and writings. The question that typically springs up to is whether or not he had pedophilic tendencies, a question that Darger’s sometimes shocking depiction of nude or partially nude children brings quickly to our contemporary minds. And we really don’t know for sure. That being said, researchers, including some Darger biographers, have asserted that the artist’s vision of the Vivian Girls is rather progressive and powerful, leading them more towards an assumption of his idealistic visions of children as strong and capable, and less about his own personal proclivities. Truly nothing in his outward life--what little we know of it, given his hermit-like tendencies--bears out any assumption of such sexual proclivities.

Henry Darger Darger passed away on April 13, 1973, only one day after his 81st birthday. On his deathbed, he advised his current landlord to destroy all of his work--never intending it to be seen by the general public. In this way, he reminds me very much of Goya, whose Saturn Devouring His Son we discussed in a previous episode of ArtCurious. Goya’s painting was one of a number of murals completed on the walls of his private home. It wasn’t intended to be viewed or even enjoyed by anyone but himself. Darger, too, created art only for himself. But his landlord went against Darger’s dying wish, and the landlord found significant value in all the manuscripts, sketches, paintings, and clutter in Darger’s apartment. Disposing of Darger’s items wouldn’t be just throwing away junk-- it would have been the dismissal of a man’s entire body of work, a sincere and innovative reflection of his unique views of the world-- its rights and wrongs, its struggles and pain, its joys and triumphs. And his aim, to envision a world of his own making and control, one truly for his own benefit, has been an inspiration to many. Darger’s works have inspired numerous poems, books, documentaries and films, as well as his own artistic style-- called Dargerism, which is how I ended up learning of his works a few years back, in reading about contemporary artists who have followed in Henry Darger’s footsteps. There’s even an all-female indie rock band called The Vivian Girls, which is a pretty cool reference, too. Darger was an “outsider artist” before the term--for a self-taught, un-art-educated individual-- hit the mainstream, and even before “outsider” art became popular or cool. His legacy, though, has been an inspiration to so many-- a man who created his own incredible art within the four walls of his tiny Chicago apartment, for no one but himself.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal, with additional writing and research help by Rachel Whitaker. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com, and social media help is by Emily Crockett. Audio production services are provided by Kaboonki, the silliest name in superb podcasts and video. Let them help you too at kaboonki.com. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator. We’re a fully independent podcast, and we rely on sponsors and donations to keep us going, so if you enjoy this show and have the means, please consider giving $10 to help this show, and thank you for your kindness. And if you don’t have money to give, that’s okay! You can help our show as well by leaving a five-star review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen-- believe me, it makes a huge difference and helps new listeners tune in. For more details about our show, including the image mentioned in this episode today, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod.

Check back in two weeks as we continue to explore the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in art history.