Episode #67: The Coolest Artists You Don't Know: Romaine Brooks (Season 7, Episode 7)

ARTCURIOUS: Stories of the Unexpected, Slightly Odd, and Strangely Wonderful in Art History is available now from Penguin Books!

For most Americans, there’s a list of arts that they might be able to rattle off if pressed to name them off the top of their heads. Picasso. Michelangelo. Leonardo da Vinci. Name recognition does go a long way, but such lists also highlight what many of us don’t know-- a huge treasure trove of talented artists from decades or centuries past that might not be household names, but still have created incredible additions to the story of art. It’s not a surprise that many of these individuals represent the more diverse side of things, too-- women, people of color, different spheres of the social or sexual spectrum.

This season on the ArtCurious podcast, we’re covering the coolest artists you don’t know. This week: Romaine Brooks.

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts!

SPONSORS

The Great Courses Plus: Enjoy a free trial of The Great Courses Plus's entire library

MOVA Globes: use code "ARTCURIOUS" for 10% off your order

Episode Credits

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Social media assistance by Emily Crockett. Additional writing and research by Joce Mallin and Stephanie Pryor.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits

"Attempt 7" by Jared C. Balogh is licensed under BY-NC-SA 3.0; "It isn't time to get up yet..." by Julie Maxwell is licensed under BY-ND 4.0; Based on a work at http://www.juliemaxwell.com/; "February" by Kai Engel is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "Dark Matter" by Podington Bear is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; Based on a work at http://soundofpicture.com/; "die frau in schwarz" by Stephan Siebert is licensed under BY-NC-ND 4.0; "May" by Marcel Pequel is licensed under BY-NC-SA 3.0 US. Ads: "Free Time" by Mela is licensed under BY-SA 4.0 (Mova Globes) .

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and further resources

The Art Story: Romaine Brooks

Smithsonian American Art Museum: The Art of Romaine Brooks (exhibition website)

Hyperallergic: A Lesbian Artist Who Painted Her Circle of Women at the Turn of the 20th Century

NPR: Painter Romaine Brooks Challenged Conventions In Shades Of Gray

Episode Transcript

What is avant-garde art? What would you call the edgiest works being made now? How about 100 years ago, during the first chunk of the revolutionary 20th century? When many historians and lay people alike think about the avant-garde artists who were making and breaking art in the early part of last century, our minds go straight to people like Picasso, Duchamp, Malevich, Kandinsky, and more- people (mostly men) who were moving incessantly towards abstraction, away from representing the world and the individuals surrounding them, or at least not representing them in a realistic or naturalistic way. But can a portrait--a recognizable image of a real-life person-- be avant-garde, can shake things up, can be truly new and different? Sure. And I’m going to tell you why.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. In season seven, we’re uncovering the coolest artists you don’t know, and today, we’re glimpsing the incredible unconventional and non-conforming portraits of Romaine Brooks. This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

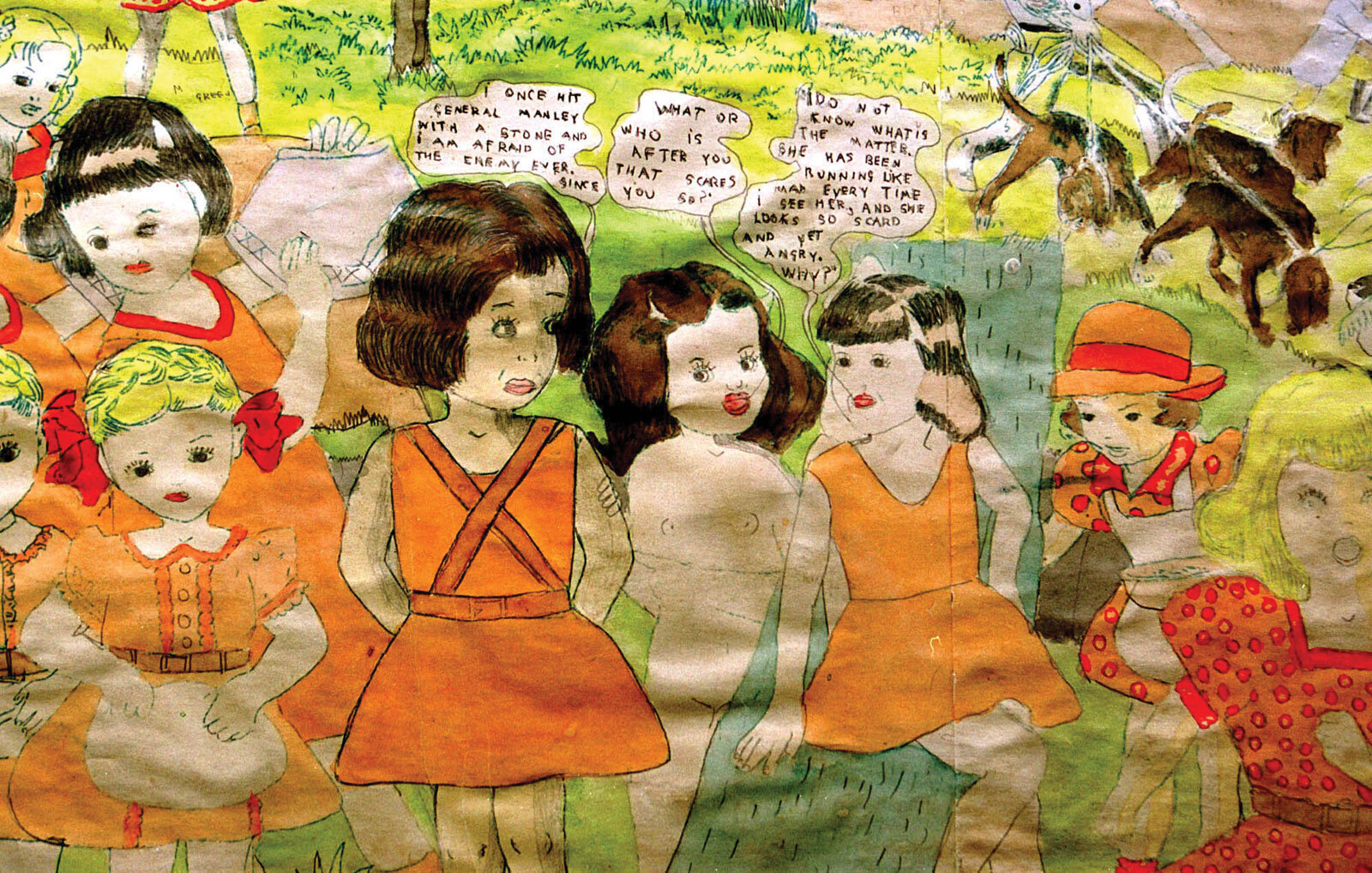

Romaine Brooks is a relatively unknown artist to most folks. And I’m not ashamed to say, hey, you know what? She was unknown to me, too, until, like, a couple of years ago. But I guess I can’t be totally blamed for my ignorance, because, like many women of her generation and beyond, she does not appear in most art history survey textbooks. And she wasn’t the star of many major art exhibitions, though she was honored with a career retrospective at the Smithsonian in 1970, which was the same year that she died-- at age 96! Though little known outside of smallish art circles, she rubbed shoulders with European aristocracy and other prominent figures from the 20th century, creating enticing and engaging portraits of many a familiar face, created frequently in an androgynous or gender non-conforming style. It’s something that put Brooks outside of the mainstream during her lifetime. And now it’s about time to bring her into the fold of art history as an artist truly meant to be explored in our own time.

Beatrice Romaine Goddard, whom we’ll refer to as Romaine, was born on May 1, 1874, to a wealthy American family living in Rome. From this line alone, you may think that little baby Romaine had it made, had entered cleanly into the good life. Nope. Her early life was marked repeatedly by tragedies both great and small. Her parents divorced while she was very young, with her father going on to essentially abandon his family entirely. Romaine was thus raised mainly by her mother, who transferred the family to New York, but her mother was unstable and distant, and went on to emotionally abuse her daughter, all while giving all her love and attention to Romaine’s brother, St. Mar, who was mentally ill and whose own emotional issues meant that he was prone to violent physical outbursts. In some ways, then, it made what happened next a small blessing, if not an ideal situation-- just before the age of 7, Romaine was abandoned by her mother, who went to Europe to live with St. Mar. Romaine was left behind, fostered with a laundress and her family in a tenement of New York City. Her mother stopped providing for her entirely after a brief period of time. But Romaine’s foster family, though poor, had something wonderful: love for their little Romaine. Even in the midst of financial hardship, they cared for her as if she was their own, and encouraged her joyfully in her early interests, especially one in particular: drawing. Even though her so-called foster family was therefore able to sustain their new charge, they still knew that some family contact--any biological family contact-- would be a good thing, so after a search, they located Romaine’s grandfather, Isaac S. Waterman, family patriarch and a multi-millionaire businessman. At first, Romaine was terrified-- she assumed her grandfather would force her to live back with her abusive mother. But instead, Waterman took on the role of provider for her, sending her to boarding school and giving her the education she needed to make her own way in the world.

And make her own way she did. In 1893, at the age of 19, Romaine moved to Paris. Initially music was her primary focus, and what little allowance she received from her family was used to pay for voice lessons. She made little money in this realm, however, living in squalor for a few years and bolstered only by the occasional singing gig at a cabaret before another calamity hit: Romaine discovered that she was pregnant. She was just 23, and this was 1897-- surely not a wonderful time for a young woman to find herself unwed and expecting a child. She gave birth to her daughter in February of that year, and made what must have been an excruciating decision to leave her baby behind at a convent for her care. But surely she needed to, to be able to afford to support herself, especially with such little family wealth sent her way. And so, she decided to return to the city of her birth-- Rome-- to study visual art with the intention of supporting herself through painting. She moved to the Eternal City later that year.

We’ve spoken many times on the ArtCurious Podcast about the various difficulties that female artists have had to face throughout history, including the problems with securing an education to sufficiently address the needs of a woman hoping to make it in the big leagues as a working artist. Luckily, Romaine was working just before the dawn of the 20th century, so art education was more egalitarian than in the past. That being said, she was the only woman in her life drawing class, for example, because it was still deemed --ahem, an issue--ahem-- for women to draw from a nude model. So she already stuck out like a sore thumb on that end. But even worse, she began to be the target of sexual harassment by several classmates. Not that she was unable to take care of herself, though. There’s a fantastic story about her strength and sass, wherein one day, she entered the art studio to find a book left open on her stool with several pornographic passages underlined for her attention. Rather than blushing, horrified, at the untoward discovery, she snapped up the book and used it to hit her perpetrator squarely in the face. Now that’s awesome. The crappy part, though, is that it didn’t really work-- she continued to be harassed, and the same porn-providing classmate stalked her and attempted to force her into marriage. Brooks escaped, taking up residence on the Italian island of Capri and struggling to the point of starvation before she received more bad news: her brother, St. Mar, had died. Thus responsible for the care of her grieving mother, Romaine Brooks returned to New York and familial duty.

Less than a year later, Romaine Brooks witnessed the death of her own mother from complications of diabetes and other ailments. The death, though, may have been a relief-- a cutting of the family ties that were so painful to her. And truly, it was a life-changing moment for Romaine, as she inherited part of her mother and maternal grandfather’s estates, meaning that the poverty of her childhood and the extreme struggle of her early adult years was finally coming to an end. At the age of 27, Brooks moved to Paris, relocating to the super-chic 16th arrondissement, a rather sophisticated part of town. And it was at this point that she began moving in the world of the uber-wealthy, where she received major commissions for portraits, especially from many of the rich women around her. But by 1904, she was looking for a change-- not in career or subject matter, but in artistic style. The first thing to go was color-- the bright, expressive colors she previously used in her portraits. Instead, she transitioned to gradations of, well, gray. After this time, almost all of her paintings are in tones of gray, black, and white, with only brief or minute touches of colors to the canvas, such as the occasional earth tone or tiny pop of teal. Inspired by folks like James McNeill Whistler, Charles Condor, and our old ArtCurious Pal, Walter Sickert, Brooks’s images became startlingly fresh, cool, and oh-so-modern.

More on that coming up next, right after this break.

In 1910, Romaine Brooks had her first solo show, at the renowned Gallery Durand-Ruel, the same gallery that so successfully supported the Impressionists and many other avant-garde artists before her. At the show, she displayed 13 paintings, almost all of which depicted women or girls, dressed in the feminine fashions of the day: bonnets, parasols, and veils of the Belle Epoque. Interestingly, Brooks included two female nudes in this group of paintings, which was a rare choice for many female artists at the time-- how scandalous! How avant-garde! Both of these works-- called The Red Jacket, and White Azaleas, both from 1910, portray nudes in quiet, dark, domestic settings, adding an air of intimacy to each scene, but Brooks doesn’t shy away from her subjects’ sexualities here: in The Red Jacket, the model is clothed in the titular covering but the jackets flaps are wide open, so that you have no choice but to have your eyes drawn directly to her breasts. And White Azaleas presents a woman laid out on a couch or divan in a frankly erotic pose that some, at the time, compared to Manet’s shocking Olympia, which we discussed in episode #41. You can imagine, given the expectations placed upon women, and female artists, at this time that this wasn’t exactly a welcome addition to a lady’s art exhibition. But Brooks was fierce in her independence and proud of her achievements. The art history website and resource TheArtStory.org begins their great article on Romaine Brooks with one of the artist’s most famous quotes, which directly links to this exhibition. Brooks said, quote,

"I grasped every occasion no matter how small to assert my independence of views. I refused to accept slavish traditions in art, and though aware it would shock, I insisted on marking the sex-triangles of all my female nude figures...."

Sadly, between the surprise of the nudes and her other psychologically intense portraits, the exhibition didn’t bring Brooks the great success she hoped for. Even Brooks’s so-called “friend,” the poet Robert de Montesquieu, called her a “thief of souls” for her unsentimental and frank portraiture. Such criticism, combined with a growing disillusionment with Parisian high society, (who frequently asked her to do interior design consultations, quel horreur) grew to a fever pitch, with Brooks referring to herself as “une lapidée,” or a victim of stoning.

Not everyone understood or “got” the way that Romaine Brooks wanted to present women in her paintings. Brooks’s ideal woman was thin and elongated. Traditionally, the female ideal had been more voluptuous than Brooks’s women. In comparison to Eve from Rubens’ famous the Fall of Man, the women in Romaine’s works seem thin, gaunt, and fragile-- something highlighted further by the artist’s use of gray and the somber colors to which she gravitated. There’s nothing bright and effusive or energetic about a Romaine Brooks portrait. Even more fascinating is her interest in challenging other conventional norms about gender depiction. Romaine Brooks was a cisgender bisexual, and her images of herself, such as the stunning 1923 self-portrait now at the Smithsonian-- more about that in a second-- and images of her friends and lovers, definitely don’t look like other portraits of women from this time period. Take, for example, her World War I masterpiece, The Cross of France, which presents her then-lover, the actress and dancer Ida Rubenstein, in a heroic and graceful turn as a battlefield nurse draped in a voluminous Red Cross uniform and suffused with an androgyny far ahead of its time. Though Romaine’s art did not directly formally engage with avant-garde movements of her time, such as Cubism or Dada, her own work is still avant-garde in its option to show a different side of womanhood-- one that went against the grain of most traditional feminine displays. This image, by the way, scored a lot of press for Brooks, as she agreed to reproduce it in a booklet sold to raise money for the French Red Cross, a highly successful fundraiser that eventually won the artist a prestigious cross of the Legion of Honor.

Gender fluidity and sexual freedom were common among Brooks’ social circle, particularly in France, where she continued to work and socialize and where she would meet the partner who most influenced her life and work: Natalie Clifford Barney, a writer and poet who would spend fifty-plus years in a relationship with Brooks. Brooks and Barney met around 1914, and while their relationship had its ups and downs, as all relationships do, it is remarkable to note that these women remained devoted to one another for the vast majority of their lives. Romaine Brooks paid tribute to her partner in a gentle 1920 painting, called Miss Natalie Barney, “L’Amazone,” or The Amazon, which presents her lover in a broad fur coat huddled against what appears to be a winter landscape, possibly as seen through a window. Like all of Brooks’s portraits, there is a sense of androgyny here, but there’s a little special addition that makes this painting stand out on its own: a small sculpture of a galloping horse added to the lower right side of the canvas. The reason for this inclusion is noted by the title, referring to Barney as an Amazon. Like the mythical race of women warriors from ancient Greece, Brooks thought Barney was a powerful, wild free spirit-- a horse that runs onward and cannot be broken. Of course, Barney liked horses and loved to ride them, too, but Brooks’s loving addition of the horse statue here isn’t that pat. It’s a proclamation of love for a woman who seemed larger-than-life to her, as powerful and mesmerizing as all those kings, dukes, and knights of years ago who had their own equestrian portraits.

Most of Brooks’ painting subjects in the late 19-teens and beyond into the 1920s came into her life due to the connections she made with Natalie Barney, with whom she hobnobbed with people like including Truman Capote, Eyre de Lanux (an American artist, writer and designer), Renata Borgatti (an Italian musician and Brooks’ lover), and Hannah Gluckstein, known as Hannah Gluck, a gender non-conforming British painter. And the portraits that she did of many of these figures, especially of and in conjunction with Hannah Gluck, show the group’s predilection for elements of male dress. This was both very on trend for the time, but also had a particular symbolism for these women. In general, women’s fashion changed in the 1920s and an androgynous, masculine look became popular throughout Europe, the United States, and beyond. The flapper dress, for example, which debuted in 1926, was formless instead of curve-hugging, and was designed especially to highlight--or at least flatter--a flat-chested physique. Many flappers also gravitated towards the bob, a short haircut that many considered masculinizing at the time. And, with the dawn of smoking as a popular, if still novel, pastime among women, the move towards something akin to gender non-conformity was as complete as it could be for the early 20th century. For Romaine Brooks, Hannah Gluck, and others, it was a boon, because within Parisian lesbian culture, using women wearing elements of masculine dress was a way to signal their independence, as well as their sexual availability to one another. Examples of this can be seen in many of Brooks’s works from this period, including but not limited to her wonderful portrait of Gluck, fascinatingly titled Peter, a Young English Girl, a work and title that specifically confuses gender in a wonderful way. Romaine Brooks’s own self-portrait from 1923 presents the artist in her typical dark, subdued palette, wearing a man’s riding outfit replete with a tall riding hat and leather gloves. While it shows us the kind of clothes that Brooks gravitated to wearing in real life in Paris and beyond, the way her eyes are shaded, slightly obscured by the brim of her hat, is psychologically profound. She looks directly at us, the viewers, but that veiling suggests something-- is it that she is hiding her true self, her true desires, from us? From the outside, such masculinized portraits appeared as very fashionable and trendy, but the deeper meaning, the subtle coding, was lost on most contemporary viewers.

All of this was fabulously revolutionary for the Modern era. Romaine Brooks was one of the first artists to create art specifically for a female gaze. Generally, in the history of art, images of women were created for men and the male heterosexual gaze, meaning that they were meant to be appreciated, or objectified, for and by men. Even art created by women sometimes fell into this same “male gaze” territory, with both sexes gravitating to creating art showing women as attractive, and as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male gaze. Brooks, though, created for a female gaze and not from the perspective of what a man might find desirable, something against the artist herself balked during her lifetime. Throughout her lifetime, she did what she wanted, painted how she wanted to paint, and dressed how she wanted to dress. When, at the beginning of the 20th century, Romaine had briefly married gay British musician John Brooks-- a yearlong partnership forged out of convenience for both in a time of great misunderstanding and bias against and about homosexual relationships--Romaine, who took her husband’s name, was subject to his complaints about her donning of masculine dress, saying he was embarrassed to see her wearing men’s clothing in public. Though she temporarily stopped dressing in this manner to appease her then-husband, she returned to it after their divorce and carried it on throughout the rest of her life.

The years following World War II were difficult for Romaine Brooks. Though she worked during the war and after--especially having been drawn to create Surrealist-inspired works during the 1930s--her production precariously tipped lower and lower. Having fled France during the war, she holed up in a villa near Florence, Italy, where Natalie Barney would eventually join her in self-imposed exile from the war. When the war ended, Brooks declined to move back to Paris with Barney, and instead stayed in Italy, where she became increasingly reclusive. It was at this point where signs began to point to her failing health and increasing mental problems. Towards the end of her life, she opted to stay in her bedroom for several weeks at a time, proclaiming all sorts of illnesses, especially grieving her poor eyesight. She also became increasingly paranoid that someone was stealing her drawings and trying to poison her, and even cautioned Natalie Barney at one point to avoid even communing with the plants, especially trees, in her garden, lest they, quote, “suck us dry” unquote, of life force. Fearful, ill, and alone, she finally stopped responding to visits, calls, and letters from friends, even Barney, and she passed away in 1970 at the age of 96 at her home in Nice, France.

The works of Romaine Brooks were just beginning to be reexamined around the time of her death and continued to grow in acclaim throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Since then, she has been lauded as a modern-day Sappho, rightly seen as celebrating gender non-conformity, making art for a gay female gaze, and creating new images of strong, non-binary, non-gender conforming persons. Brooks portrayed her subjects as strong, powerful, and confident, thereby heroizing them. In explaining the “development” of art history we often seek artists who confirm and conform to paradigms that we have created through bias. Romaine Brooks does not follow the zeitgeist of her day (bright colors and abstract approaches) yet her art was avant-garde for the time, and she deserves a place in the canon for pushing social boundaries and celebrating lesbian culture in Paris in the twentieth century.

Romaine Brooks is an example of how artists can be marginalized within the field of art history, and how traditional approaches to art history often cannot properly accommodate the complexities of the field of art history.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal, with additional writing and research and writing help by Joce Mallin and Stephanie Pryor. Also check out our friends at theartstory.org for lots of excellent, free content all centered around art history. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com, and social media help is by Emily Crockett Audio production services are provided by Kaboonki, the silliest name in superb podcasts and video. Let them help you too at kaboonki.com. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator. We’re a fully independent podcast, and we rely on sponsors and donations to keep us going, so if you enjoy this show and have the means, please consider giving $10 to help this show, and thank you for your kindness. And if you don’t have money to give, that’s okay! You can help our show as well by leaving a five-star review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen-- believe me, it makes a huge difference and helps new listeners tune in. For more details about our show, including the image mentioned in this episode today, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod.

Check back in two weeks as we continue to explore the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in art history.