Episode #68: Katsushika Ōi (and Hokusai)

ARTCURIOUS: Stories of the Unexpected, Slightly Odd, and Strangely Wonderful in Art History is available now from Penguin Books!

For most Americans, there’s a list of arts that they might be able to rattle off if pressed to name them off the top of their heads. Picasso. Michelangelo. Leonardo da Vinci. Name recognition does go a long way, but such lists also highlight what many of us don’t know-- a huge treasure trove of talented artists from decades or centuries past that might not be household names, but still have created incredible additions to the story of art. It’s not a surprise that many of these individuals represent the more diverse side of things, too-- women, people of color, different spheres of the social or sexual spectrum.

This season on the ArtCurious podcast, we’re covering the coolest artists you don’t know. This week: Katsushika Ōi: i (and her father, Hokusai).

Please SUBSCRIBE and REVIEW our show on Apple Podcasts!

SPONSORS

The Great Courses Plus: Enjoy a free trial of The Great Courses Plus's entire library

Campfire Poetry: Support independent artists in their endeavor to bring poetry to new audiences

Indeed: Try Indeed out with a free $75 credit

Native: Use our link or use promo code artcurious at checkout for 20% off your first order.

Episode Credits

Production and Editing by Kaboonki. Theme music by Alex Davis. Social media assistance by Emily Crockett. Additional writing and research by Adria Gunter and Stephanie Pryor.

ArtCurious is sponsored by Anchorlight, an interdisciplinary creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle.

Additional music credits

"Phoenix" by Circus Marcus is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; "Peaceful Mind" by Borrtex is licensed under BY-NC 4.0; "owl's secret" by The Owl is licensed under BY-NC-ND 4.0; "Le 13ème travail d'Astérix: Endormir les tout-petits" by Circus Marcus is licensed under BY-NC 3.0; "Interception" by Kai Engel is licensed under BY 4.0. Ads: "In Shadows" by William Ross Chernoff's Nomads is licensed under BY 4.0 (Campfire Poetry); "Sinking Feeling" by Jesse Spillane is licensed under BY 4.0 (Native); "Acid Jazz" by Kevin McLeod is licensed under BY 3.0 (Indeed)

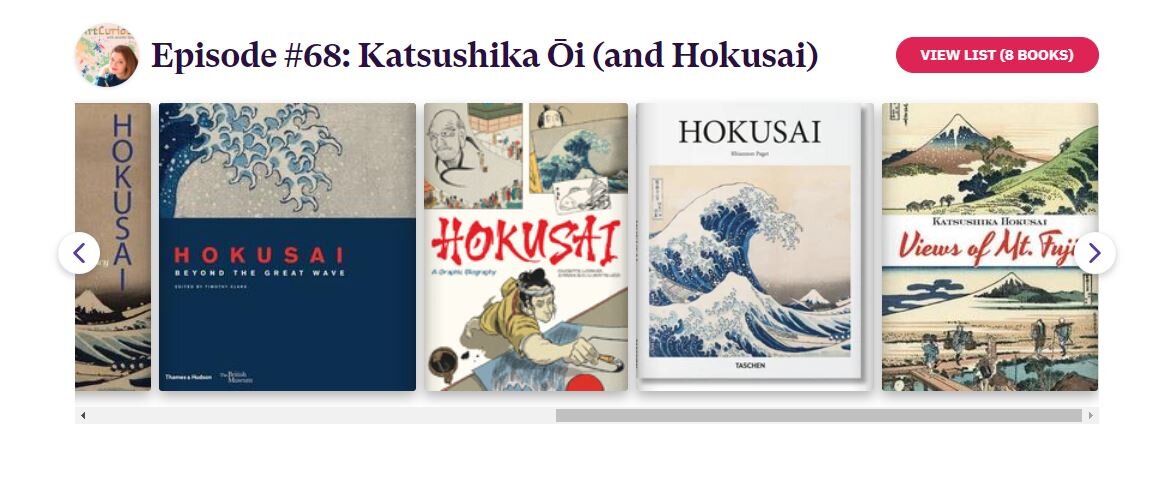

Recommended Reading

Please note that ArtCurious is a participant in the Bookshop.org Affiliate Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to bookshop.org. This is all done at no cost to you, and serves as a means to help our show and independent bookstores. Click on the list below and thank you for your purchases!

Links and further resources

The British Museum: Hokusai and Ōi: art runs in the family

Christie’s: 10 Things to Know about Hokusai

Katherine Govier, “Ōi without Hokusai//A Woman Artist is the Floating World”

Episode Transcript

One of my favorite things about doing this podcast is that it gives me a way to continue to learn about art, and especially to learn about art that is not always in my wheelhouse. During my days, I focus on contemporary art with what I hope is a wide and global emphasis, but as many of you know, my training wasn’t so broad. That’s the thing about going to grad school, about pursuing specific degrees-- you end up getting very narrow in your focal area. But with ArtCurious, it doesn’t have to be so specific. And that’s what’s been so rewarding about this season, about what we’re calling “The Coolest Artists You Don’t Know.” Because in some cases, the “you” in that season title was actually me, too. And that is especially the case for the artist we’re discussing today for our season finale. She was all-new to me. And for an art nerd like me, there’s almost nothing more thrilling than the discovery of an exciting, fresh artist.

Some people think that visual art is dry, boring, lifeless. But the stories behind those paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs are weirder, crazier, or more fun than you can imagine. In season seven, we’re uncovering the coolest artists you don’t know, including an artist whose existence I only learned of a couple of years back-- the artist-daughter of a famed Japanese superstar. For our season finale, we’re uncovering the life and work of Katsushika-Ōi.

This is the ArtCurious Podcast, exploring the unexpected, the slightly odd, and the strangely wonderful in Art History. I'm Jennifer Dasal.

Like many, many, many of the artists we have repeatedly discussed on this podcast, Katsushika Ōi was never a stranger to the art world because she had a familial link to this world: her father was an artist himself. But this story is going to be different right off the bat than those of other women like Rosa Bonheur, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Angelica Kauffman, and so many others, because the fame and influence of those women have outstripped the careers of their own fathers. But not so here, for better or for worse, because Katsushika Ōi’s father was none other than Katsushika Hokusai, one of the world’s most recognized and revered Japanese artists of the modern era-- if you’ve heard of him, you probably know him just as Hokusai, his given name. And if you aren’t familiar with Hokusai by name, it’s nevertheless practically a certainty that you’ve seen his best-known work, a print called The Great Wave off Kanagawa, also known as just The Wave or The Great Wave, an image of a white-capped wave curling magnificently over three long boats with Mt. Fuji standing sentinel in the distance. As far as Japanese artists are concerned, especially before our contemporary period, Hokusai is probably the biggest, and definitely one of the most recognizable. By the early 19th century, he had reached the zenith of his career, finding interest for his landscapes and images of everyday Japanese life, for which he became most widely known. These illustrations were featured in many books and print collections, but his work didn’t stop there-- he also published a number of instructional art manuals, and released twelve volumes of manga, or Japanese graphic novels, during this period, a format that is even more popular now than it was back in Hokusai’s day. So, you know, not a small act for his daughter to follow. But what’s amazing about Katsushika Ōi, whom I’ll simply call “Ōi” for this episode, is that she was truly able, nonetheless, to carve her own successful path outside of her father’s influence, a feat that was nearly impossible for women in Japan at the time.

Much of Ōi’s life is a bit of a cipher, as might be expected for a woman born in the early 19th century. We don’t know her exact birth date, but historians have assumed that she was born somewhere around 1800 to Hokusai and his second wife, Kotome. The family lived during a period in Japan known as the late Edo period, also known as the Tokugawa period, or the final era before the massive reform and industrialization of the later half of the 19th century, which changed Japan forever. The Edo period is what some have referred to as the last breath of quote “traditional Japan.” Just a little bit of context here.

Ōi’s given name was actually “Eijo,” but it looks like she ended up changing her given name early on in her career, or perhaps she opted to adopt a variation of it, or a nickname instead. Either way, her name choice-- either Ōi, spelled O-I, or Ei, spelled E-I, is a testament to the playful, teasing relationship that existed between herself and her father. Some accounts noted that Hokusai would often refer to his daughter by the informal and somewhat jokingly impolite name of Ōi, which roughly translated, in modern English, to “hey you.” It’s telling that she would go on to adopt this cheeky name, but it makes sense, too, as someone whose own livelihood was molded and assisted by her father’s own hand. He trained in her father’s studio alongside her siblings-- three sisters and a brother-- so that each learned the basics of painting and printmaking from a very early age. But it was noted that Ōi was, by far, the most artistically-talented and knowledgeable of Hokusai’s children, and such aptitude would serve her, and her father, very well.

It’s difficult to discuss Ōi’s life without gŌing deep into her father’s life, too, because they are inextricably linked, and because Ōi appears to have acted for her father in many cases. In the 1820s, after the death of her mother, Ōi assumed a caretaking role for her father, who was then in his late 60s. After so many years of training at his knee, she was primed to assist him in carrying out commissions and other private projects, often signing his name instead of hers to works of art that she created-- though whether or not she was doing this to masquerade as her father, or to use his name as a kind of family-identifier or because he was just a bigger name and it was easier that way-- it’s all up for debate. Ōi likely signed her father’s name to most works because Hokusai had a more globally- recognized name, which we’ll get to in a moment, and society in Edo-era Japan, as in most of the rest of the world, was staunchly patriarchal.

But it is interesting to note that it was during this time that Hokusai was in the midst of painting his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, his most iconic series, and the one which would go on to include The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Knowing what we know now about Ōi’s talents and abilities and the roles she played in assisting her father throughout his career, some historians have gone on to wonder just how much of works like The Great Wave were actually painted, in part or in full, by Ōi instead of her father.

I alluded a moment ago to the global fame that Hokusai experienced during his lifetime. Though much about Hokusai’s life is mythic and difficult to ascertain-- the lines between fact and fiction are blurred, even more so than in Edmonia Lewis’s life, which we explored earlier this season-- there seems to have been one probable meeting between the Japanese artist and a German doctor named Philip Franz von Siebold, a man employed at a Dutch trading post in Nagasaki in the 1820s and who went on to commission some works from the artist. When Siebold brought these works back to Europe, they were met with fervor from an already burgeoning “Japanomania,” or “Japonisme,” as it was called, an absolute adoration for all things culture and art from the still-closed-off-from-the-West country. You can especially see evidence of this fervor in the second half of the 1800s, when artists like Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh took cues from Japanese art, especially prints like those done by Hokusai, for their own art. What’s interesting is that the connection between Siebold and Hokusai may have been facilitated by one of the artist’s assistants, as it has been long noted that Hokusai was injured during this period and would not have been available to meet with von Siebold to discuss and plan commissions. Was his daughter, Ōi, responsible for this career-making endeavor? Possibly. Such questions do much to show us that Hokusai’s key connections and collaborations with his daughter were more than incidental-- they were essential to his career.

Naturally Hokusai’s fame and talents must have helped Katsushika Ōi in her career, too-- but as her life progressed, her renown--separate from that of her father--grew, too. That’s coming up next, right after this break.

Welcome back to ArtCurious.

If Ōi was actively adding to her father’s fame, the good news is that she also began to add to her own. By the 1820s, he began to venture out on her own, making artwork of her own accord and in a realm specifically apart from her father’s. Most notably, Ōi capitalized on a highly-popular painting genre called bijinga, which roughly translates to “portraits of beautiful people,” and Ōi trained her bijinga brush on portraits of women in particular. Bijinga appears to have been a wonderful mishmash of styles and influences, encompassing such disparate elements as advertising and classical painting, pop culture and parody. As doctoral candidate Anna Moblard Meier noted in a 2013 exhibition essay on bijinga, “Edo-Period bijinga advertised the latest hairstyles and textile designs, the plays and celebrated actors of the kabuki theater, specific teashops and performance arenas in Edo, and the ‘entertainment women’ and festivals of the yoshiwara, Edo’s licensed brothel district.” Unquote. This last part is notable, but not shocking-- the women depicted in Ōi’s pictures are typically courtesans. Prostitution was legal in Japan during this period and played an important role in Edo culture. Though it surely wasn’t a happy profession for many, it was nevertheless a segment of society that was prized and idealized-- an area which fed directly into the visual arts of this period. Ōi's most famous work of art is Night Scene at Yoshiwara, a print that depicts the main red-light district of Edo. Ōi’s talent is masterfully evident here, a colorful image defined by the contrast between light and dark, showcasing the decorated courtesans on display in a brightly lit room while spectators peer in on them from the night-dimmed street beyond. What’s fascinating here is the psychological tone of this artwork. It’s pointedly different from other examples of Ōi’s bijinga output. Take, for example, her works that more directly venerate feminine beauty- Three Women Playing Musical Instruments, which dates from between 1818 and 1840 and is now on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. I mean, the title itself is pretty self-explanatory here, but you’ve gotta hand it to Ōi-- she’s an incredible painter. Her detailing of the textures and colors of the women’s clothing, for example-- that alone is magnificent. And in another silk hanging, called Beauty Viewing Cherry Blossoms at Night, or just Cherry Blossoms at Night, now at the Menard Art Museum in Komaki, Japan, is even more stunning in its combination of female depiction and a celebration of the natural world. Here, too, you can see those same preoccupations with contrast of light and dark and of color and detail-- but that street scene in Yoshiwara is just… different. It’s more theatrical, like the courtesans here are placed on a stage set, the actors in a play that isn’t necessarily of their making. The disconnect is heightened further by the fact that we, as viewers, are with the spectators on the outside, and we look in on them through the wooden latticework of windows. Now, it’s hard, as a 21st century American to put myself in a position of understanding the cultural specificity of this scene and to assume I understand any of what the courtesans, let alone the artist herself, is feeling or thinking in creating such a scene. But to me, that latticework feels very reminiscent of bars of a jail cell or a cage. Was there any consideration or question, on Ōi’s part, that these women appear more like animals in a cage than human beings? Maybe. But probably not-- and that’s the conflict here. Is she simply memorializing a specific tradition here in Yoshiwara? Is she objectifying these women? Is she applying some kind of proto-feminist undercurrent to her painting, a reminder of the suffering or injustice that was likely fŌisted upon them? That’s a lot for us to consider, and probably we’re reaching here. And yet in comparison to her other bijiwara images, which are more evocative of fashion plates than anything else, this one captures a darkness that is both literal and figurative.

As her success in the bijinga genre continued to flourish, Ōi’s independence from her father’s artistic influence was becoming more apparent - while Hokusai had mostly veered away from figurative painting, his daughter was making a career out of it, and was doing so quite successfully. Hokusai was undoubtedly proud, once noting, quote, “When it comes to paintings of beautiful women, I can’t compete with her-- she’s quite talented and expert in the technical aspects of painting.” Unquote. But to minimize Ōi’s works to this focus on beautiful women is to further minimize her technical prowess, too. In addition to Night Scene in the Yoshiwara, Ōi’s other masterpiece is Operating on the Arm of Guan Yu, a painted scroll from the 1840s that depicts a gruesome, bloody scene from a 16th-century Chinese novel called The Romance of Three Kingdoms. In this scene, the legendary military leader Guan Yu undertakes a bloodletting in order to potentially remove poisons inflicted upon him by an enemy’s arrow. The expressions here are priceless. While his attendants’ bodies writhe in discomfort and most of them turn their heads, barely able to witness the rivulets of blood pouring out of their leader’s sliced-open arm, Guan Yu rather humorously remains fully attentive to the board game in front of him-- and behind him, an abundant meal awaits. It’s basically like he’s just chilling on a normal evening, no big deal, just getting his arm methodically sliced open, la di da. It’s fantastic. And Ōi’s mastery of the 19th-century Japanese painting genre is obvious here, an achievement made even greater when we consider that, at nearly 55 inches tall by 27 inches wide, this is the biggest known work by the artist. And yet her shrewd attention to detail in everything, from the intricate designs on the garments worn by the men to the fine, red lines flowing from Guan Yu’s arm is exquisitely executed. Ōi counterbalances chaos with composure, contrasting the obvious violence of the bloody scene with the elegant and spare interior surrounding her figures. It takes a particularly talented artist to pull off this feat and Ōi does it wonderfully.

In the last years of her life, Ōi continued to enjoy a modicum of success and fame, though she died in relative obscurity. After her father’s death in 1849, she continued to operate his art studio alongside several other assistants, which explains the interesting anachronism of the existence of Hokusai works that date to after he died. From what little we know of Ōi in the years after her father’s death, it appears that she taught for a bit, taking pupils and assistants of her own before moving and eventually falling off the grid-- her death most likely occurred somewhere around 1866, though no one knows for sure. Like Edmonia Lewis, she disappeared from our history books due to the limitations of history and her gender, but thankfully more has been done to remember her, both as a key collaborator with Hokusai and as a hugely talented artist in her own right.

Thank you for listening to the ArtCurious Podcast. This is the last episode of our current season, so I want to thank you all for the love, support, and listening that you’ve done with us over these past few months. Rest assured that we’ll be back with you later this fall. This episode was written, produced, and narrated by me, Jennifer Dasal, with additional writing and research help by Adria Gunter and Stephanie Pryor. Our theme music is by Alex Davis at alexdavismusic.com, our logo is by Dave Rainey at daveraineydesign.com, and social media help is by Emily Crockett. Audio production services are provided by Kaboonki, the silliest name in superb podcasts and video. Let them help you too at kaboonki.com. The ArtCurious Podcast is sponsored primarily by Anchorlight. Anchorlight is a creative space, founded with the intent of fostering artists, designers, and craftspeople at varying stages of their development. Home to artist studios, residency opportunities, and exhibition space Anchorlight encourages mentorship and the cross-pollination of skills among creatives in the Triangle. Please visit anchorlightraleigh.com.

The ArtCurious Podcast is also fiscally sponsored by VAE Raleigh, a 501c3 nonprofit creativity incubator. We’re a fully independent podcast, and we rely on sponsors and donations to keep us going, so if you enjoy this show and have the means, please consider giving $10 to help this show, and thank you for your kindness. And if you don’t have money to give, that’s okay! You can help our show as well by leaving a five-star review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen-- believe me, it makes a huge difference and helps new listeners tune in. For more details about our show, including the image mentioned in this episode today, please visit our website: artcuriouspodcast.com. We’re also on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram at artcuriouspod.

While you wait for us to come back online with new episodes this fall, remember that you can preorder my new book, “ArtCurious, Stories of the Unexpected, Slightly Odd, and Strangely Wonderful in Art History,” coming out on September 15, 2020 from Penguin Books. It’ll be a great new way to connect with us, and we’re looking forward to sharing more-- until then, stay curious.